The announcement yesterday that Nigel Farage is back heading Reform UK as leader and standing in the radical right constituency of Clacton was not only a shot in the arm for his latest vehicle party, but is likely to inadvertently help every other party of consequence in tight contests in the general election except the Conservatives. The veteran leader’s sudden change of mind is probably the most consequential event of the campaign thus far, and makes clear that he comes to bury Rishi Sunak, not to compromise or acquiesce like he did in 2019 with Boris Johnson by standing down in Tory Leave areas (though it must be said that the Brexit Party’s withdrawal actually helped Labour retain about 30 seats).

The fieldwork for all of the recently released MRPs and Voting Intention polls, which have been ‘kind’ to the outgoing government, came before Farage’s return. Some political pundits speculate that his increased prominence in the campaign could see a crossover event—Reform UK overtaking the Tories in VI. I don’t share that view, but even a modest amount of direct switching from 2019 Con→2024 Con to Reform UK over and above the current levels (say 2%) would have a drastic effect on the outcome of the election. One of the unintended consequences could be to make the Liberal Democrats, fourth in voteshare in this scenario, His Majesty’s Official Opposition, mirroring events in the Canada 1993 election.

The similarities are striking: a once popular minister was thrust into leadership, but didn’t connect with voters whatsoever. The governing party cratered at the election, replaced by their red rivals in a landslide. A rival right-wing party, coincidentally also called Reform, hoovered up a lot of the small ‘c’ conservative votes. The previously popular third party collapsed, being replaced by the fourth party whose electorate was concentrated in a specific area of the country, sufficient enough to see them thrust into second and official opposition.

The implied chances of an outcome akin to what happened 31 years ago in Canada happening in the UK next month are between 10%-20%, depending on which bookies you look at. So let’s say it does happen, parliament reconvenes (without the space for many Labour MPs on one side of the aisle), and at the first PMQs, there’s the utterly surreal sight of Ed Davey sitting opposite new Prime Minister Keir Starmer, about to stand up and ask his first of six weekly questions. What would it mean?

N.B. I am mostly a sofa commentator/Lib Dem member with limited experience of knocking on doors and all that good stuff, so I’m really no more qualified than the vast majority of people to opine with conviction.

The long and the Short

A result with the Lib Dems coming second in seats on around 10%-12% of the vote probably means Labour having close to 500 on around 45%, an unprecedented skew in British politics, even under the utterly antiquated first-past-the-post system. The oranges would almost certainly have to have north of 50 seats to be in such a position, a phenomenon not seen since the dark days of coalition, but altogether completely new territory in second place. The party would receive a lot more Short Money than at present, plus a financial boost simply for being HMOO.

It’s no secret that, outside of the massive injection of donations fuelled by opposition to Brexit five years ago, the party has struggled for quite some time to attract regular, sizeable sums outside of a few people with relatively low political profiles. Being the official opposition would change this, probably not overnight as it would take a while for everyone to adjust to the new set of circumstances, but there would be undoubted interest from hitherto unreachable quarters. Perhaps some individuals and firms would gravitate away from the Tories, and lobbying would be heavier on core liberal issues such as the environment, trans rights, and renewable energy. The increased funding would still need to be carefully managed, but might perhaps leave the party less reliant on members. That contingent would also increase with the far greater prominence afforded to official opposition status, though the days of hundreds of thousands affiliating themselves in this way to any UK party are almost certainly an artifact of the past.

The three body problem

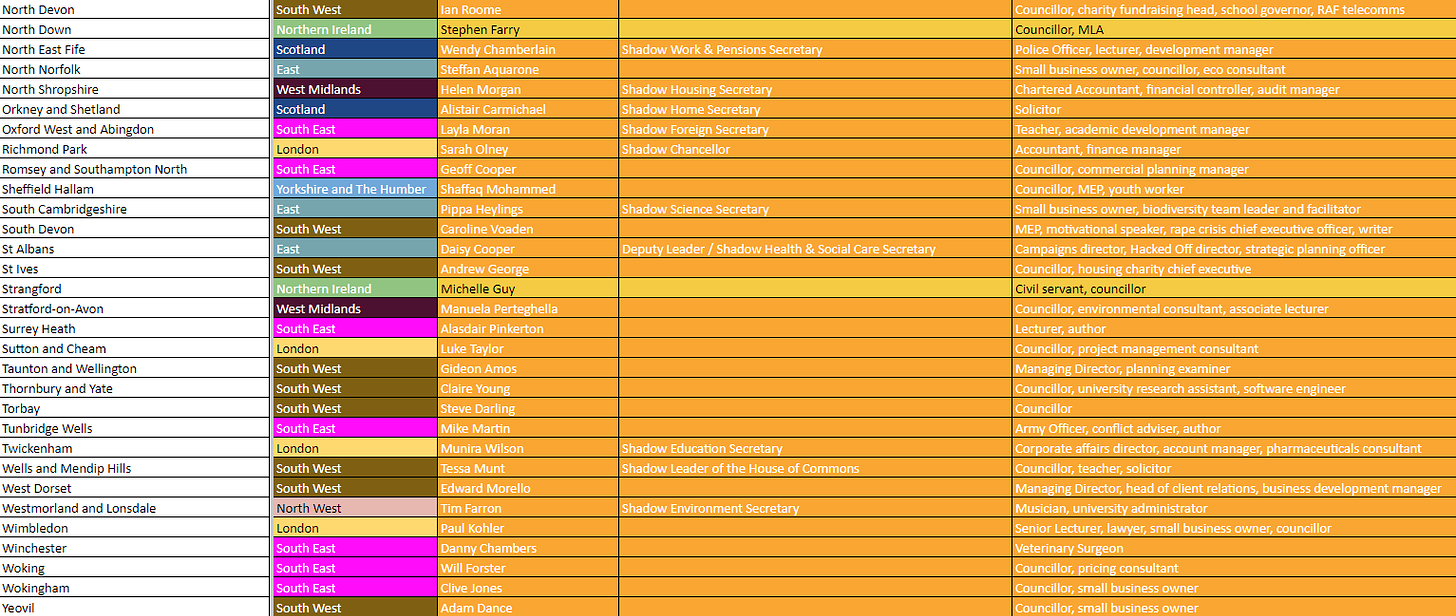

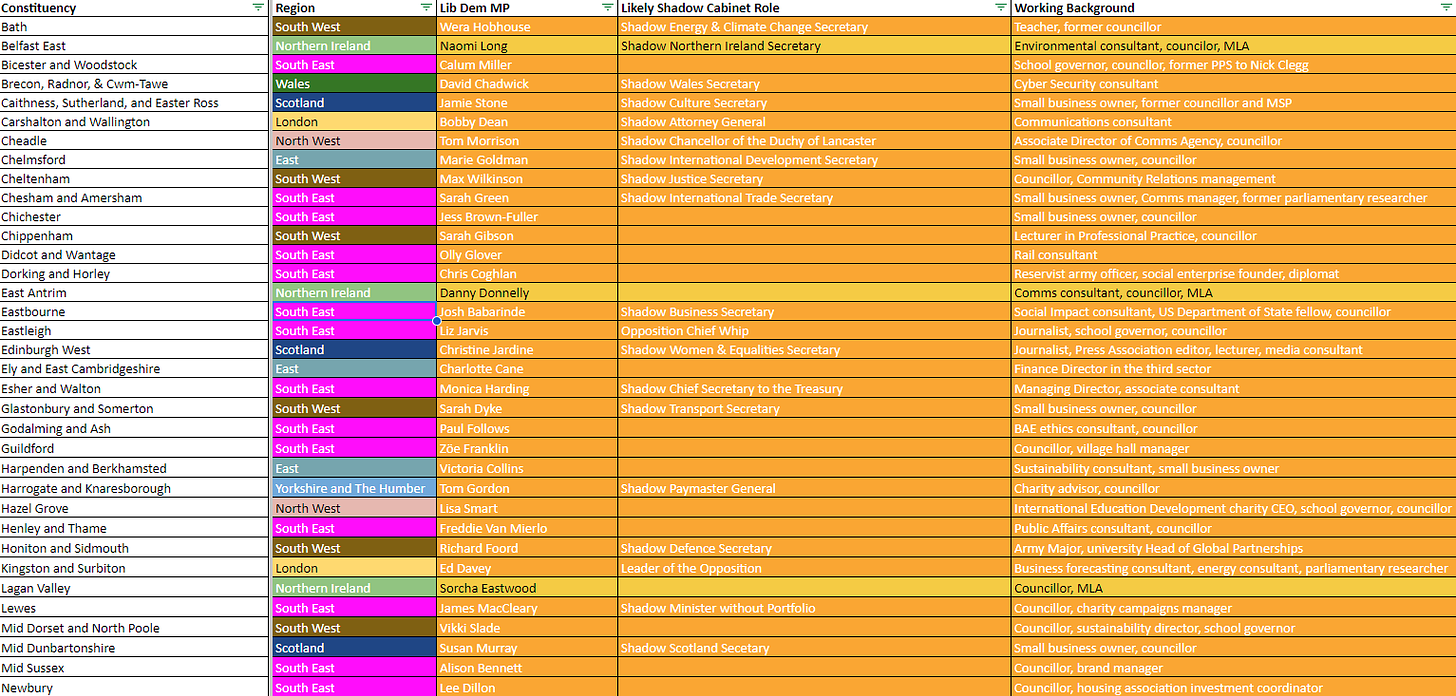

Because of the way politics operates in the UK, cabinet and their shadows are given their roles by the party leader—they’re already MPs that might have expertise in the policy areas they get assigned, but this is just as often a coincidence as it is a deliberate action. Additionally, the number of these roles has been steadily going up over the years. A cursory glance at the current Labour shadow cabinet is indicative of this trend, and also highlights a huge issue the Lib Dems would have, even if they multiplied their notional 2019 figure of just 8 MPs seven or eight times over. There simply wouldn’t be enough people in the Commons to fill all of those roles, and though some of them could be done by the grouping in the Lords, the stark reality is that a good number of MPs would have to hold two or even three briefs.

Though that issue would unlikely by itself interfere with everyday parliamentary processes, it would entail a huge mental drain on some of the more prominent figures. With a gargantuan majority, Starmer’s most difficult task in the first two to three years of a Labour government would be party management, rather than any concerns at all about getting legislation through. The sizeable rebellions Tony Blair faced in his decade of premiership wouldn’t even come close to furrowing his eventual successor’s brow. In public perception terms, this would simultaneously both a major problem for the Lib Dems and the entire opposition as a whole and a potential boon in terms of making crystal clear, more than ever before in living memory, the case for liberal solutions to ordinary people’s problems.

The following two images exemplify this:

Alliance, the ‘sister’ party in Northern Ireland and included above, could win anything from one to five MPs thanks to a combination of their own polling, the downturn in DUP support, and strong candidates in seats Sinn Féin have pulled out of. The potential exists therefore that they become the second NI party in terms of MPs, but in actual Commons representation, an outsized role because of the longstanding abstentionism of Sinn Féin alongside theoretically taking the Lib Dem whip in this scenario to help amplify this fact. There is existing precedent for this; Lord Alderdice, former Alliance leader between 1987-1998, sits in the upper chamber for the LDs.

The first elephant in the room

Ed Davey is a protégé of the late Paddy Ashdown. He worked under him for years before becoming MP himself by a wafer-thin margin in 1997. Apart from a two-year hiatus where almost every Lib Dem parliamentarian lost their seat in 2015, he’s been in the Commons for nearly thirty years, only becoming leader at the second attempt in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic. He’ll be 59 at Christmas. His home situation is well-documented, which leads me to believe that he would be highly unlikely to remain Leader of the Opposition for a full five-year term. I believe he sees his mission as the face of the party to restore them to the electoral standing they had under Ashdown and Charles Kennedy.

Having fulfilled that ambition in this scenario, few would begrudge him if he chose to step down early in the new parliament, though as already discussed, relinquishing the leadership would probably not mean an emptier schedule.

The subsequent leadership contest would have far more scrutiny than any previous ones in living memory. There’s a high chance current deputy leader Daisy Cooper would contest it, and there’s a possibility she would be joined by Layla Moran, though the ongoing situation in Gaza complicates matters. The parliamentary contingent would be replete with new MPs, and their careers of five and seven years respectively at the time of writing would make them appear to be veterans of the lower chamber.

Not only would Labour have their huge majority and an army of civil servants to help devise and implement government policy, Starmer and co would be up against a much smaller party severely lacking in experience and few levers of extra support to call upon. Of the 62 likeliest MPs, only Davey, Alistair Carmichael, and former leader Tim Farron were present before and during the coalition years, and only a handful more would have served a full term—the numbers swelled from 11 to 15 as a result of big swings in by-elections between 2019 and 2023.

There are also the not insignificant factors of disproportionately being present on select committees and maybe even having to proffer one of their contingent for a deputy speaker role to consider. This will in turn drive calls for the target seats at the next election to be widened to relieve the strain on the post-2024 cohort.

As a consequence of all of the above, the early years of the new parliament would feel like an uphill battle in more ways than one, regardless of the extra cash and prominence they would also bring.

Through the media lens

In a FPTP system, any third (or indeed fourth) party, with few exceptions, is going to have a difficult time being heard. The Lib Dems know that only too well, and the halcyon days of Kennedy railing against the Iraq war (an event that brought me into politics, as I’m sure was the case for thousands of others) or Nick Clegg being invited to the first televised debates were very much outliers. There are strict criteria broadcasters have to adhere to regarding coverage outside of election periods, and without friendly newspapers or wall-to-wall programming on television amplifying a party’s messaging, the pitch is certainly sloped against such challengers to the main two.

None of that is new. However, would there be an immediate shift if the Lib Dems were the official opposition? I’m not certain of it. Granted, the PMQs elevation (the 15 or so minutes of the least representative exchanges in any given week of the business in the Commons), coupled with appearing on Question Time on a permanent basis, would shift the dials by themselves to a certain degree, but against the backdrop of a general decline in substantive, in-depth political programming on the BBC and across the piece.

Would outsized attention still be devoted to the Conservatives’ electoral post-mortem, or Nigel Farage’s plans for Reform UK (particularly if he’s successful at the eighth attempt at winning a seat)? Probably, yes. The relentless nature of round-the-clock coverage means journalists and news channels are predisposed to abhorring vacuums or even worse, relative political stability with little in the way of real drama.

The 2024 election will be discussed and dissected for decades to come, but most people will move swiftly on from it—real issues that affect everyday lives will then become the new government’s remit to tackle, with a limited timeframe to demonstrate meaningful action on.

Reverse takeover?

Farage has deliberately failed to completely shut down speculation that he still harbours ambitions to become Conservative leader at some point after the upcoming election almost certainly leaves them a mere shadow of their former selves. Though few real safe seats now exist for the Tories, if they hold onto roughly 50 of them in this nightmare scenario, the composition won’t be much different to the Lib Dems in terms of a lack of experience, although some of the remaining contingent will have had prominent cabinet positions.

Nevertheless, it would be completely new territory for them, and the recriminations for their worst ever electoral defeat in their storied, singularly successful 200-year history will rumble on for years; the factions are already present and accounted for, and though they’ll be greatly diminished, the scramble for supremacy in the parliamentary rump could be brutal.

Though the general public are less and less attached to particular parties and many don’t think along the axes of left-right or liberal-authoritarian, it’s difficult to envisage a way the Tories could come even close to a return to government in just five or 10 years, especially with the added ‘barrier’ of the Lib Dems hoovering a lot of the attention (eventually).

Any 2024 result where Reform UK outpoll or even come close to outpolling the Tories, coupled with a commitment from Farage to stick around for the duration, would make the ‘reverse takeover’ that happened in Canada post-1993 on the right much more tenable. Farage has better polling amongst current Conservative voters than many ‘rivals’ actually in the party, and it’s not much of a leap to suggest he could be a ‘Unite the Right’ figure for a plurality, if not a majority, on the end of the spectrum of British politics.

Under such a banner, a lot of ground would be ceded to Labour and the Lib Dems in the medium to long-term in exchange for an outward united front, perhaps with a newfound zeal for proportional representation, which Farage himself and Reform UK are advocates for.

The second elephant in the room

Regardless of whether Farage attempts such a ‘coup’, the future direction of the Tories has appeared to be even further right than at present for several years now, with a radical right element imported from the USA’s ‘MAGA’ strand of Republicanism. The aforementioned vacated space would be very tempting for the Lib Dems as a party to move into, chiefly because that is where many of their serious candidates for selection are increasingly drawn from—affluent southern English seats that mainly voted Remain in 2016 where voting Labour is seen as the least palatable option.

In other words, the ever-decreasing circles of post-2015 circumstances and national relevance up to the 2024 election have made being a social liberal and a Lib Dem the preserve of people (both candidates and members) who can afford to have that mindset. The current Labour coalition of voters will also be drawn from the social liberal pool, though in areas where austerity and the Lib Dems being junior partners to the Tories for five years have had greater and longer lasting socio-economic effects.

So then, what would the policy platform be? Under Kennedy, the party attacked Labour ‘from the left’ across the piece. That possibility is not one Davey, Cooper, or Moran could draw from a generation later. Liberalism as a concept doesn’t sit well on that scale; moreover, it is facing a crisis in continental Europe just to survive in the face of increasing populism at both extremes. The UK has always been a bit of special case, however, as have the Lib Dems in terms of party/ideological classification.

With the demographics as they are, attracting a great deal more voters in the 18-24 pool in particular would be difficult even as the biggest rivals (relatively speaking) to Labour. The long arm of the tuition fees debacle saw to that, and continues to act as a drag on party perception now. Many of the students who lent their support in 2010, only to then be betrayed, will now have young families of their own, and are likely to continue to turn elsewhere in the years to come, even if or when support for Starmer’s government starts to sag.

Positive cases for drug reform, affordable housing, self-ID, better pay for carers, and greater protection for British farming interests could form the basis of a credible ‘alternative vision for government’. It is also likely that inertia alone will move a Labour government towards closer ties with the European Union, despite the current protestations about ‘making Brexit work’, so it is probably not going to be an angle unique to the LOTO.

With trust in politicians and politics low and a general desire to avoid revisiting both that referendum and the recent governmental psychodramas, the Lib Dems would do well to be ‘critical friends’ to Labour on issues where there’s a consensus between the two frontbenches, and opposing on matters of deeply held liberal principles where gaps exist between the two, playing the ball and not the person wherever possible.

The current trend towards tactical voting would also take on a very different form, especially if Labour are deemed to performed below expectations by a less tribal public.

Green Dreams

The left of Labour avenue is not credible as a Lib Dem strategy post-2024 because of the coalition, but also because of the rise of the Greens. Any election scenario where Carla Denyer and Adrian Ramsay’s party maintain or increase their toehold in the Commons is likely to become of the stories in the next parliament.

Though distinct in some ways from the 1990s/2000s Lib Dems, there are overlaps in the strategy and voter base of the modern Greens. Where the former were both the go-to protest vote/neither of the above repository for voters, the Greens are in some areas of the country already are that choice, especially in local elections. The process is certain to accelerate under the auspices of a Labour government, and any by-elections in a constituency with notionally low Lib Dem support would be seized upon by the Greens, especially towards the latter half of the parliamentary term, should there not be demonstrable improvement in most people’s living standards and bold action on climate change, though it would be a mistake to classify present day and future Green voters as only being on the left—the breadth is actually much wider, taking in environmentally conscious small ‘c’ conservative groups, too.

The narrow path

As discussed at the outset, the chances of the Lib Dems being thrust into the harsh, lonely spotlight of Official Opposition are small, but far from impossible. Should they manage to do it through a combination of their own efforts, the Labour tide, and Farage’s machinations, the path to preserving that status and growing it into anything like challengers to a Starmer hegemony is a very narrow one indeed, and many unforeseen events in the future could easily blow the party off that course.

Politics is ultimately about gaining power to affect people’s lives, hopefully in the vast majority of cases for the better. Second place would mean it would be that little bit closer, and hopefully silence the ‘what is the point of the Lib Dems and what do they stand for?’ questions for good.